s08e19: Why design experiences, when you can design states of mind?

0.0 Context Setting

Look, just remember to stretch, OK? It’s no fun turning forty and then suddenly not being able to walk for half a day due to excruciating pain in your foot that turns out to be most likely planar fasciitis, which in the great scheme of things is much better than worrying you’ve suddenly developed a blood clot, given *waves hands* what’s happening right now.

I’m writing this (actually, finishing it — I started it a good month ago) on Thursday, August 6, 2020.

1.0 Some Things That Caught My Attention

1.1 Digital Psychology

Boy, do I have a story to tell you today. As ever, this bit is an adaptation of a series of tweets from this morning.

Last (Friday) morning, before I’d even had breakfast (or, if we’re being brutally honest, before I’d really gotten out of bed), I made this mistake of taking a brief look at a notorious “hacker” “news” site to see if there was anything that would catch my attention or, more likely, annoy me. I was not let down!

Today’s thing that caught my attention is digitalpsychology.io, a “free library of psychological principles and examples for inspiration to enhance the customer experience and connect with your users” (my emphasis).

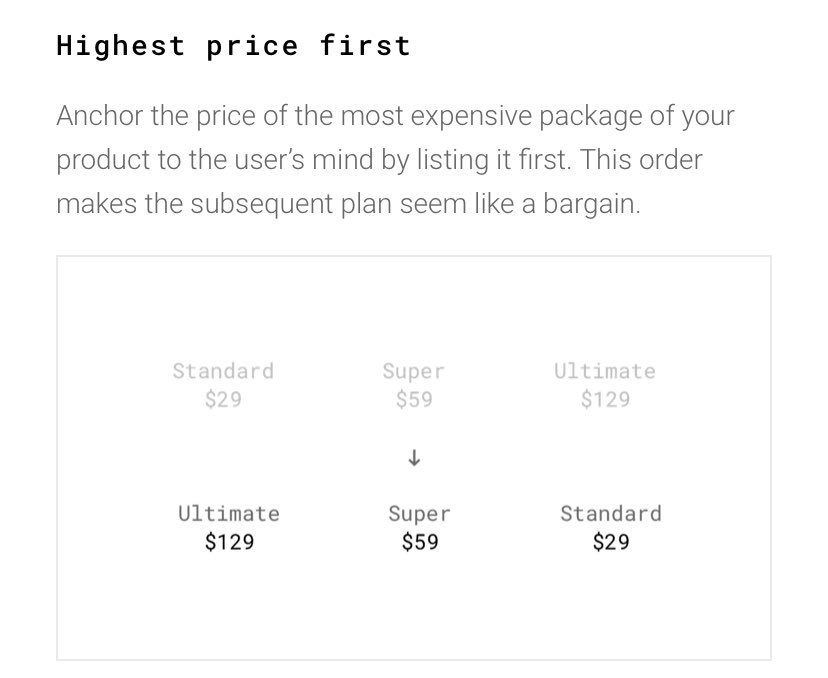

Reader, I looked at the site and did I have Comments. It was of examples from cognitive psychology and behavioral economics (many of which have failed to replicate). Here’s the first one that struck me, your basic regular anchoring example:

Like I say: does making a plan seem a bargain enhance a customer’s experience?

There was more, of course. Another example was to use quantity limits, where adding a limit may increase the number of average items in a purchase:

Again, my credulous face: how is doing this enhancing a customer experience? It felt awfully like doublespeak to me, where my customer experience would be very much enhanced by having just one more wafer thin mint that I really, really, really didn’t want to have.

Another example, then, this one about how you can use loss aversion to make pepole feel bad about not completing a purchase:

There are more, but my favorite one to include in this part is about how you can increase the response rate for cold emails. I like to call cold emails spam.

So far, so standard, right? Go see an annoying thing on the internet first thing in the morning before eating anything, take a skim through it and get Super Outraged, tweet about it, and after a few examples the structure of the bit requires that you point out these are all dark patterns, i.e. “tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn’t mean to, like buying or signing up for something.”

So off I go, Internet Crusader, Righteous Righter Of Moral Wrongs In The HTTPSpace and pull Daniel Stefanovic, the creator of the website, into my thread, asking him if he knows about dark patterns, pointing out that the top comment on Hacker News calls out the site for “using pop psychology to manipulate your customers into spending money and giving you personal information”, adding a link to an Association for Computing Machinery ethics case study on dark UX patterns, and just for good measure, a link to Evil By Design, a talk from IXD 2019.

Look at me, doing my internet call-out take-down of Someone Not Being Ethical On The Internet.

Now, I’m going to out myself here. I did the looking-up-a-person thing after I started the thread. Stefanovic puts his name and Twitter account on the site, but it didn’t look like he’d tweeted for over a year. He didn’t appear to be active anywhere else. And then I got a bit worried and sheepish: maybe the site, which I then found out had launched in 2018, hadn’t been updated because something had happened to Stefanovic?

No matter, I’d already decided to tag him in on the thread.

And then I go have breakfast, go have a call with the wonderful Sarah Szalavitz (of which more later, in the Next Part), and I open up Twitter on my phone and see this:

and this:

Which, honestly, blows my mind with all of the heart emojis.

Because, really, in 2020 I wasn’t expecting someone to listen to criticism (especially criticism in my mind that was tinged at least the tiniest bit with snark and a hint of meanness) in such a way and respond openly and thoughtfully.

So there you have it. A nice, heartwarming internet story. Lesson for me: less of the snark. Or, at the very least, not snark all the time.

1.2 It’s Simple And Complicated, But Ultimately Simple

I had an overdue conversation with Sarah Szalavitz on Friday about a bunch of things that turned out to be mostly related, but I can probably parcel out into discrete chunks.

Sarah and I started talking because I asked her for feedback on my thoughts on MIT’s search for a new Media Lab director; Sarah is a friend who was a fellow at the Media Lab in 2013, teaching a course on Social Design.

Sarah wasn’t able to talk, er, I guess what people call it at press time, but we ended up talking after she’d had time to gather her thoughts. My apologies to Sarah if I get anything wrong in writing about what we talked about.

One big piece of feedback that I got from my criticism of the job posting and description from many people was that the would be considered for tenure at MIT requirement was not-so-subtle coding for we don’t want a Joi Ito again.

Because Joi was one of those outsiders, he didn’t have that academic record (and yet, was able to earn honorary recognition during and after his time at the Lab, precisely because he was now at the lab).

And yet Joi by all accounts was tremendously successful at attracting funding for the Lab and MIT. He was—is—a consummate pitch man, selling a vision of the future in just the same way that Nic Negroponte did at the outset of the lab. But I think with maturity and hindsight now (at least for some of us, I fully believe that there were many people skeptical at the time who were not listened to), many of the promises of the Lab are convincing enough dreams that are probably not going to ever see the light of day. If I’m being generous (and I’m sympathetic to this), they are things to strive for that we may never reach, but nonetheless may push us further in directions that we might not otherwise have chosen to explore. If I’m not being generous, those visions are in the area of lies or distractions. I hate to equivocate about this, but I do think that where we are and need to be is, sigh, somewhere in between.

I very much regret not seeing the coding for not Joi in the academic requirements. I have to admit that I was quite upset (which is English for absolutely spitting furious) as I read the post and job description and missed that part. It makes absolute sense to me, and I figure it’s the kind of error that results from writing from the hip and just shooting something off. That’s something I’m thinking about as I practice my writing here and figure out what I want to do, and what I want to get better at.

But I digress: Sarah’s point about the academic requirement was that if you kept it, instead of what I was advocating for, then many of the most qualified people, those people with PhDs in the relevant subject areas for what the Media Lab should become, would likely be Black women. And yet removing that requirement would put them at a disadvantage.

So our conversation then went to what felt like the inevitable: does the Lab, and by extension MIT, actually want to change? It is, after all, an institution. The lab is 35 years old now. MIT is positively ancient for an American educational institution, founded in 1861 and 159 years old now. If MIT wanted to change, then what would that look like? The make-up of faculty would be different. They would hire differently. They would make decisions instead of have committees, which is clearly not specific to MIT, but one inherent to any institution old and mature enough to want to protect itself.

And why might the institution not want to change? Why not say the simple thing and not dissemble? Why not just say: we need a fundraiser. We need someone who can get out there and sell a vision and get money so we can do our thing. Because that is a very different job. And then you get into perhaps the complicated part, which is, well, when it comes down to it, which one is more important? The work and the outcome, or the money through which you have the means to deliver the work or the outcome?

(I’ve got a bit below where I argue this isn’t that complicated. It is only complicated when you choose to make it complicated).

There’s another point to this that was raised by Sarah and others who gave me feedback: maybe the Media Lab doesn’t need to exist? Certainly collaboration is good (such an anodyne statement that I can’t imagine anyone seriously arguing against it), but perhaps what’s needed is a more distributed Media Lab across, well, all of MIT?

Or perhaps MIT’s Media Lab doesn’t need to exist any more, and a thousand more need to bloom across the world?

The header for this part was originally “It’s Simple And Complicated”, but in the end I changed it to “It’s Simple And Complicated, But Ultimately Simple”. I updated it because what I feel is important to hang on to is the clarity. I think sometimes things are complicated because we wish not to make a difficult decision and we prefer the path of least resistance. It is actually simple to say that we want an institution that does not have to compromise itself in the way that the Lab and MIT does in terms of funding sources.

It is actually simple to say that we want an equitable institution that seeks to serve all and is serious about accountability and consequences.

It is not complicated. (I imagine there are lots of people getting ready right now to say that no, I’m not being a realist, the question of funding is very complicated). It might be hard and it might be difficult and it might require making some uncomfortable decisions, but those come from what is ultimately a simple decision. And I know it is easy for me to sit on the outside and throw commentary and opinion like this. I know that there is only so much money and only so many places that it may come from. But those places — like Epstein — may not be ones sources we are prepared to use. That, I’d say, is a simple decision and then the rest following from that is necessarily constrained. So we don’t have Epstein levels of money. Great. Then there are other things we can do, and we may be limited in resource so there are other things we cannot do.

I’ve been reading Emily Nussbaum’s collection of essays on television, I Like To Watch, which I can’t recommend highly enough. (It isn’t just about television at all). When Nussbaum writes about poetry by Pearl Cleage and Cleage’s push to find clarity and draw lines instead of blurring them when talking about how Miles Davis abused his wife. Here’s how Nussbaum writes about Cleage’s poetry:

[Cleage writes] “How can they hit us and still be our heroes?…Our leaders? Our husbands? Our lovers? Our geniuses? Our friends?”

She concludes with two sentences. The first is “And the answer is…they can’t.” The second is, “Can they?”

Some of us so frequently look for the can they and skirt past considering the much simpler they can’t. Why don’t we?

2.0 Some Smaller Things That Caught My Attention

I saw this tweet quoting Macieg Ceglowski about the longevity of data:

… and I think the problem is actually worse. The data itself collected around people has the potential to last for a long time similar to nuclear waste — or, even worse. The data can outlive the institution that manages it not just because of its physical properties, but because right now, it exists in a market environment that puts value on it. It will continue to be bought and sold and passed on and, unlike nuclear waste, copied. It can proliferate.

But I’d argue that in some ways, long-lived personal data is even worse than nuclear waste. While the data itself may live, the context which makes the data understandable and useful decays much more quickly because it likely [citation needed] has not been collected. Frequently what may make data valuable is the environment and context in which it was collected, and that context and metadata gives the collected fragment of personal data meaning. Otherwise it is potentially just a piece that can be misinterpreted because it is no longer in situ.

Devoid of context, or worse, misinterpreted into an inaccurate context, or one purposefully inaccurate, the longevity of discrete pieces of personal data might mean that its potential for harm actually increases over time as the context in which it was collected decays.

OK, that’s it for this episode. More later!

Best,

Dan